Remarkable how many stock-market patterns lead to enhanced returns—until you put them to use.

How are investors doing with “factors”—those financial attributes that drive a stock’s performance?

If factors are destined to succeed as stock-picking tools, that’s terrific news. It means you can retire rich without doing a lot of work managing a portfolio. If they fail, they will illustrate an important truth, which I will get to at the end of this essay, about trying to beat the market.

It’s too soon to render a final verdict on factors—that will take another 40 years or so—but my preliminary reading is that factor-based investing is going to be a flop.

Before being commercialized on Wall Street, factors were an academic concept. Professors would dig through a mountain of stock returns, looking for patterns. They found some. It was interesting work. It generated several Nobel Prizes.

The original factor, discovered by Harry Markowitz in the 1950s, was beta. Stocks in companies with high risk (by dint of either their line of business or their leveraged balance sheets) would display a high beta coefficient when you regressed their returns against the returns of a market composite. Over time, so went the theory, high-beta stocks would beat low-beta stocks.

Does that theory hold up? Sort of. Provided that you can withstand high volatility, a high-beta portfolio will probably deliver a high return. But high-beta stocks don’t accomplish anything you can’t get by buying merely average stocks using borrowed money. So the beta insight has not given rise to investor wealth.

A decade after Markowitz did his seminal work, Value Line, publisher of of a widely read investment survey, introduced a new weekly ranking system that told its subscribers what stocks were hot. The system had several components, but essentially boiled down to momentum investing. It capitalized on the fact that stocks of companies that were delivering positive earnings surprises and that had recently outperformed would tend to outperform for a while longer.

The ranking system delivered magnificent results—on paper. Value Line calculated that a hypothetical investor following its recommendations for the first 22 years would have enjoyed capital gains averaging 23% a year. That was almost triple the collective number for the 1,700-stock universe in the Value Line Investment Survey.

Beat the market with a mechanical rule? That would fly in the face of the efficient-market hypothesis, the idea that stock returns are a matter of luck. Economist Fischer Black (of the Black-Scholes option formula), a fan of EMH, was in awe. He described the Value Line system as a perplexing anomaly.

In real life? A different story. Value Line opened a mutual fund that aimed to hold a constantly updated portfolio of top-ranked stocks. The fund was a fiasco. It didn’t even keep up with the market average, much less the market-beating hypothetical return.

What went wrong? In buying newly upgraded stocks, the fund manager was paying prices prevailing after survey results were released and was competing with investment survey subscribers. The paper performance was based on something very different, prices recorded two days earlier. It turned out that almost all of the survey’s excess returns took place in a few days surrounding the publication date, and was not something that investors could get their hands on.

After beta and momentum came the size factor. A famous 1981 paper that had started out as a Ph.D. dissertation declared that, over long periods, small-company stocks vastly outperform big-company stocks. That revelation gave rise to a stampede among money managers to create small-stock portfolios.

The small-stock anomaly, alas, vanished as quickly as it was discovered. For the years 1927 through 1981, according to a database of stock returns maintained by market theorist Kenneth French, stocks in the smallest market-value quintile zoomed ahead, with an 18.1% annual return versus 8.6% in the large-cap quintile. Since then the two quintiles have been in a dead heat at 12.6%.

The academics kept delving, and kept discovering anomalies. They seized on such factors as quality (shares of companies with nice balance sheets and fat margins outperform), value (stocks trading at low multiples of earnings or book value outperform) and low volatility (sleepy stocks outperform on a risk-adjusted basis). And in every case there were marketers on Wall Street ready to cash in with new products.

The academic studies were valid, in that they accurately identified investing styles that looked good in hindsight. That is, you could have gotten rich off them had you only known to implement them at the beginning of whatever period was being researched. That is not, however, the same as saying you’ll do well after the anomaly is revealed.

Factor investing reached a fever pitch several years ago with a proliferation of what are now called “smart-beta” fund portfolios. You knew we had reached a manic peak when even Vanguard, that paragon of passive investing, joined the gold rush.

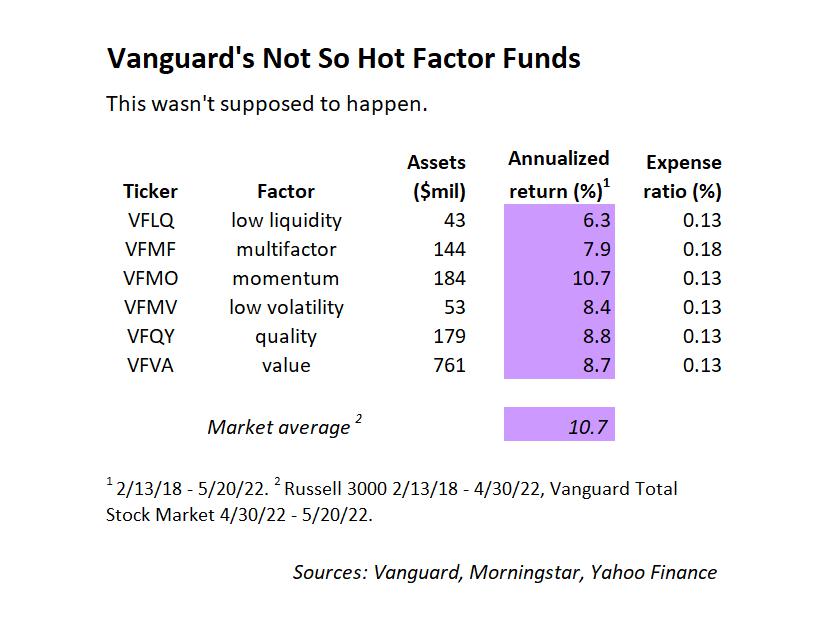

In February 2018 Vanguard opened the doors on six factor funds. There are five basic flavors: momentum, quality, value, low volatility and low liquidity. (The last, a close cousin of the size factor, assumes that investors have to be rewarded for putting up with obscure stocks.) There is also a tutti frutti fund that combines the first four flavors in a single portfolio.

How have they done? Not well. In the 4-1/4 years since, the momentum fund, which owns stocks like Nvidia and Tesla, has eked out a tie with the market. The other five have fallen behind. The flagship multifactor fund’s annual return is running 2.8 percentage points behind the market’s.

It wouldn’t hurt to buy these losers now. My prediction is that, after their slow start, the Vanguard funds will make up some lost ground and will, over their first 40 years, exactly tie the market, just as small stocks have tied big ones over the past 40 years. But then, if you want to tie the market, you could save yourself a lot of trouble by getting an index fund.

All this leads to a simple lesson about not just smart beta but every other market-beating scheme. I lift it from a prescient 1982 Forbes article poking holes in the theory that small stocks would always beat big ones. The wording has the fingerprints of an editor known for his skepticism about Wall Street fads, but, since both he and the author are deceased, I will never know which of the two should get the credit.